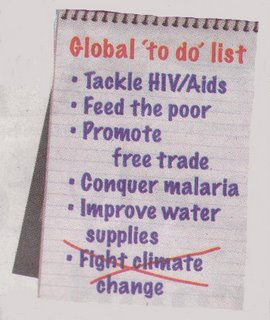

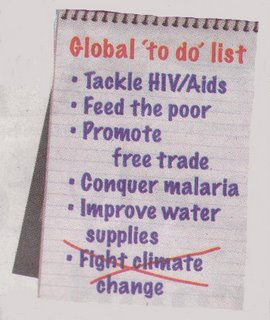

Bjorn Lomborg, publicity-shy economist, statistician and climate change sceptic, is busy pushing his new book "How To Spend $50 Billion To Make The World A Better Place". The number-crunching Peter Schmeichel lookalike has written up the findings of his Copenhagen Consensus think-tank in a format that we mere mortals may find more accessible. In a Comment article in last Sunday's Observer ("C limate Change Can Wait. World Health Can't") he continues his campaign to persuade us that money spent on combating climate change is wasted. Following on from his 1998 best-seller "The Skeptikal Environmentalist", his core message is that we will get much better value from investing in the areas of human health and economic development than in measures aimed at reducing or mitigating the impacts of human-induced climate change. But still missing from his work is any idea that the environment has value in its own right, rather than as a life support system for the human race.

limate Change Can Wait. World Health Can't") he continues his campaign to persuade us that money spent on combating climate change is wasted. Following on from his 1998 best-seller "The Skeptikal Environmentalist", his core message is that we will get much better value from investing in the areas of human health and economic development than in measures aimed at reducing or mitigating the impacts of human-induced climate change. But still missing from his work is any idea that the environment has value in its own right, rather than as a life support system for the human race.

Lomborg is the master of the misleading book title. In "The Skeptikal Environmentalist", he proved that he is by no stretch of the imagination an environmentalist. His new book should be called "How To Spend $50 Billion To Make The World A Better Place For The Human Race, And Stuff Every Other Species". limate Change Can Wait. World Health Can't") he continues his campaign to persuade us that money spent on combating climate change is wasted. Following on from his 1998 best-seller "The Skeptikal Environmentalist", his core message is that we will get much better value from investing in the areas of human health and economic development than in measures aimed at reducing or mitigating the impacts of human-induced climate change. But still missing from his work is any idea that the environment has value in its own right, rather than as a life support system for the human race.

limate Change Can Wait. World Health Can't") he continues his campaign to persuade us that money spent on combating climate change is wasted. Following on from his 1998 best-seller "The Skeptikal Environmentalist", his core message is that we will get much better value from investing in the areas of human health and economic development than in measures aimed at reducing or mitigating the impacts of human-induced climate change. But still missing from his work is any idea that the environment has value in its own right, rather than as a life support system for the human race.For the full text of the Observer article, go to observer.guardian.co.uk

To add your comments to the debate on how to give the planet a $50bn makeover, go to

www.observer.co.uk/blog

6 Comments:

Thank you for your thoughts Robert. Good to have some input regarding the environment economics approach as this is a growing discipline/approach (eg. carbon trading).

My initial response is this (although I didn't create the original post);

I think your post looks to present a number of arguments on how to approach discounting. I'm not sure the services that a forest provides (for example), other than timber and tourism, can realistically

be valued and therefore discounted for various investment options. Trying to value the Amazon for health products is obviously ludicrous because of its vastness and the lack of knowledge of what's in it. The Amazon's role as a part of the globe's oxygen/CO2 cycles is impossible to value in economic terms. Even if a figure was put on it, it couldn't be used because the margin of error would measure in the trillions! Hardly useful economics.

The overall argument of valuing a forest for its human required services therefore leaves huge gaps in its calculations when the other services that I have mentioned above cannot be accurately valued. It becomes a useless guessing game and not much use for informed economic decisions.

The pound/yen/dollar cannot always rule when it comes to making 'resource use' vs 'natural state preservation' decisions. Larger issues of population growth and the rate of resource use and waste generation need to be factored in as it is these areas that need attention.

Matt Burge

Sorry being so long in responding, this is pretty esoteric stuff and I don't want to make a complete tit of myself.

Robert, you said that I'm wrong in arguing that Lomborg's analysis skirts the issue of the intrinsic value of the environment. Not so much an argument as a statement of fact. Of all the items on the Copenhagen Consensus' shopping list, only climate change has any bearing on the non-human. All the rest are aimed at improving the human condition. Ecological health and resilience? Not important, unless it improves delivery of human-specific ecosystem goods and services.Biodiversity? Forget it. In fact Lomborg applies the same sort of twisted logic to biodiversity loss as he does to climate change. Since we don't know the exact proportion of change that is down to human activity, it's pointless trying to do anything about it. A bit like the occupants of a small sinking boat arguing about fixing the hole because they don't know how much of the water in the boat is down to the leak and how much to the waves coming in over the bow. Answer: it doesn't matter, just fix the hole.

I agree with Matt in having difficulties with the idea of assigning monetary value to 'nature'. There's something else I have trouble with: how does cost benefit analysis really help us choose options aimed purely at human health and affluence. How do we know the marginal utility of another thousand, or million, or billion human beings? Do we actually need to allow the human population, and its associated consumption and waste, to increase still further?

All good points, now that I've read what you've said in the cool of morning!

As a biologist would tell us, all species have population limits. Humans would be foolish to ignore this. Nature determines this for us through disease and resource limitations. I do agree that poorer people have every right to what wealthier people have access to and most human beings will strive for better. It's in our nature. It doesn't mean they will achieve it. One reason being that it's also in our nature to compete (for resources). This is why there are more wars in the world right now than ever before.

Obviously the rate of consumption/capita in the 'west' is high and other countries such as India, Brazil and China are fast catching up.I doubt consumption rates will slow for some time. The 'gadget' is God. One of the biggest problems is that the quality of goods production has dropped off the cliff edge. Price drives everything but nothing lasts anymore. Externalities (which are still on the whole left out of market prices) must be imposed and enforced globally by the UN to provide an economic level playing field. This has to include some sort of guidance on acceptable product lifecycle periods and waste costs need to loop into this. Economic sanctions must be the enforcement tool for countries not enforcing at national level. Companies should also register to do business with a UN database/agency. If they don't comply they could be fined and ultimately have their trading licence taken away from them. Those producers that invest in reducing externalities (e.g. emissions) will win out.

I've extended the arguments a little as I think we've all done the Lomborg thing. I personally wouldn't give him the time of day.

Well, it seems Matt has got bored with Bjorn Lomborg; short attention span these Kiwis! 8-)

However, since it was my post originally I'll take the liberty of giving him one last mention. Enlightened folk like thee and me may not be prepared to "give him the time of day", but sadly a lot of people in high places don't feel the same way, including the UN. http://www.prnewswire.com/cgi-bin/stories.pl?ACCT=109&STORY=/www/story/06-09-2006/0004377598&EDATE=

I feel quite strongly that, whether you agree with Lomborg or not, he is an influential figure whose activities need to be monitored. That's why, in the cause of "Know Thine Enemy", I own a copy of "The Skeptikal Environmentalist" into which I often dip during my studies just to see what the opposition has to say about an issue. Incidentally, for the same reason I also have a copy of Michael Chrichton's awful eco-thriller "State of Fear". Lousy novel, pretty poor science, but a wonderfully eclectic bibliography.

Yup, 'The best form of defence is attack' Israeli Defence Force (IDF).

To add to my second to last point; regarding driving externalities affecting the environment into production costs, the level playing field that I have suggested be administered at UN level should be administered via stock exchanges. Reasons being that they already have the power to suspend bad conduct and secondly there is the new trend of stock exchanges merging across borders. This may help deal with the problem of national governments getting in the way of encouraging a more level playing field for enforcing environmental laws. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea is one such example of how environmental laws can be administered; http://www.un.org/depts/los/index.htm

Post a Comment

<< Home